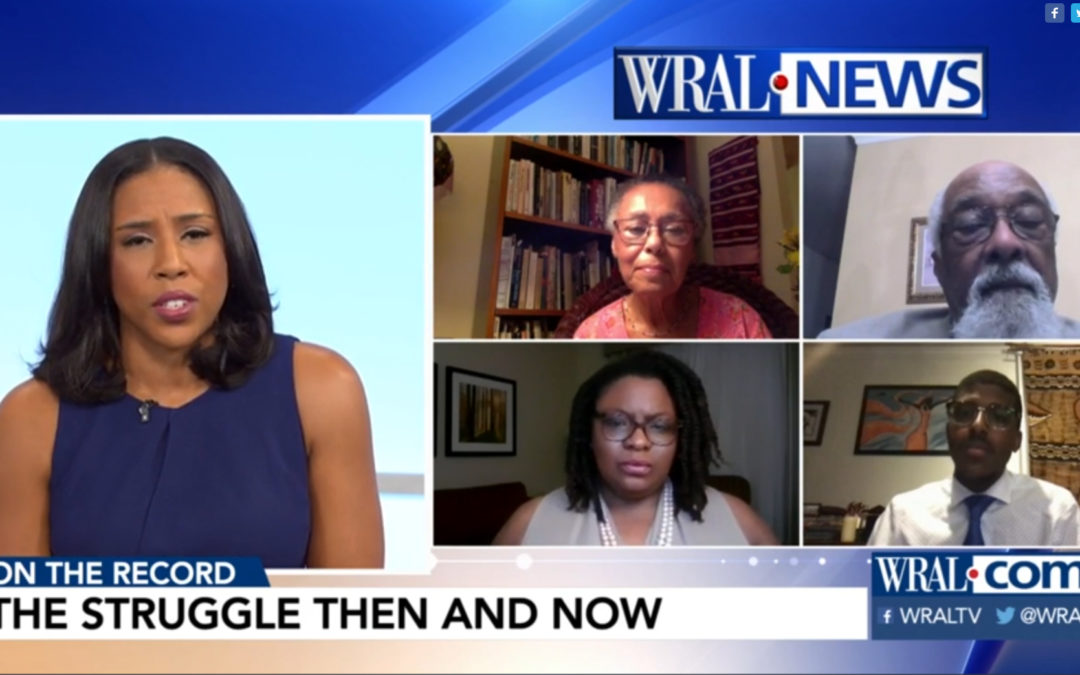

On August 15, WRAL’s Lena Tillett hosted a powerful segment connecting the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 60s to today’s Black Lives Matter activism and protests. Tillett brought together a Zoom panel of experienced activists across different generations:

- Judy Richardson, who served on the SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) in the 60s and producer of the PBS documentary “Eyes on the Prize”

- Professor Irving Joyner, an author, civil rights litigator, and law professor at NCCU

- Emancipate NC’s Executive Director Attorney Dawn Blagrove

- Ajamu Amiri Dillahunt, PhD student and activist with the Black Youth Project

The conversation began with reflections from Richardson and Joyner. Richardson was quite young when began her work as an activist with SNCC, travelling from New York to Deep South at the age of 19. Richardson shared memories of connecting with a well-organized and courageous community, which both inspired her and helped her feel as safe as possible in what was a very dangerous time and place for activism.

“We were surrounded by Miss Ella Baker, who was our legendary strategist… our guiding light. She puts us in contact with her network… and they are the ones who guide us and guard us. I am looking around at people who are courageous beyond anything I’ve ever known,” reflected Richardson.

Professor Joyner then noted that in the 50s and 60s, the South had been identified as the place with the worst racism, and many activists came from the North to the South to organize and mobilize. Joyner reminded listeners that the civil rights movement then didn’t have the same level of legal protections – nor the support from Black politicians, officials, and legal talent – that the movement has today.

“Most importantly, you didn’t have social media. You had the mimeograph machine and foot leather that you had to get out on the corner to pass out leaflets to encourage people to appear. Then you had organizations that put together demonstrations… now you don’t need organizations. You just need a Twitter account,” said Joyner.

Blagrove shared how she is seeing a tendency for modern society to deify the leaders of the past, and historically romanticize and oversimplify the movement as an individualized struggle that largely achieved it goals. She also sees parallels between the activists of then and now.

“Today’s young activists still have the same passion. It comes from the same place. There are some truly revolutionary ideas that are being put forth by many in this movement. However, there is a steep learning curve about how to take those ideas and revolutionary thoughts and transform them into policies and put them into place,” said Blagrove.

As a student activist today, Dillahunt also noted strong connections between both movements.

“Both movements are rooted in the struggle against racism, white supremacy, and capitalism that the United States has been committed to since its founding, and seeks to further develop in the contemporary,” said Dillahunt.

Dillahunt shared how activists like him are grateful for the ability to inform their current efforts with the vast amounts of historical research, autobiographies, and first-hand testimony from the civil rights era.

“We’re unique in that we have lessons to draw on from those who actually participated back then,” said Dillahunt.

The discussion continued with a deeper dive into how both movements have been portrayed both in the media at the time and in historical contexts. Richardson discussed the how the movement started out with a strong belief in nonviolence as a philosophy, but eventually as those leaders left or were killed, nonviolence became more of a tactic aimed directly at saving lives.

“Our main goal was trying to get Black people registered to vote without getting them killed. You don’t want to do anything that will call down the power of the state upon you. We were tactically nonviolent, because we didn’t want to endanger not just our lives, but the lives of everyone around us,” reflected Richardson.

Blagrove then tackled the topic of how widespread and varied today’s movement has become.

“What we are seeing now is a whole wide array of different ideas and radical thoughts about how to address a problematic system of institutional and structural racism. Options run the gamut from total abolition to various reforms. The reality is that all of those options exist on the same continuum. There is space for all of them and there will be a time for all of them,” reflected Blagrove.

When asked if today’s movement seemed less organized and more geographically dispersed, Blagrove agreed, but quickly added that it had an important positive effect as well.

“We shouldn’t characterize this movement as chaotic, we should call it fruitful,” Blagrove replied.

Professor Joyner added that some of the more spontaneous actions of the 60s, which were often characterized as riots, got more response than the organized, nonviolent actions.

“It’s important that we keep moving forward, no matter what. It’s not chaos, it’s creativity,” said Joyner.

Dillahunt followed up with thoughts about the current intergenerational and visionary direction of today’s movements.

“The struggle for revolutionary change is a process. Part of that is getting people to envision a new world, and reimagine not just how to end police violence, but how our entire society is structured and how we’re governed. We want a world where everyone gets to make decisions about their lives, and not just a select few,” said Dillahunt.

To listen to the full discussion, we invite you watch this powerful segment at WRAL.